note

Waterfalls, Wheels, & The Editorial Process

It's time to expand the scope of editorial beyond post-production

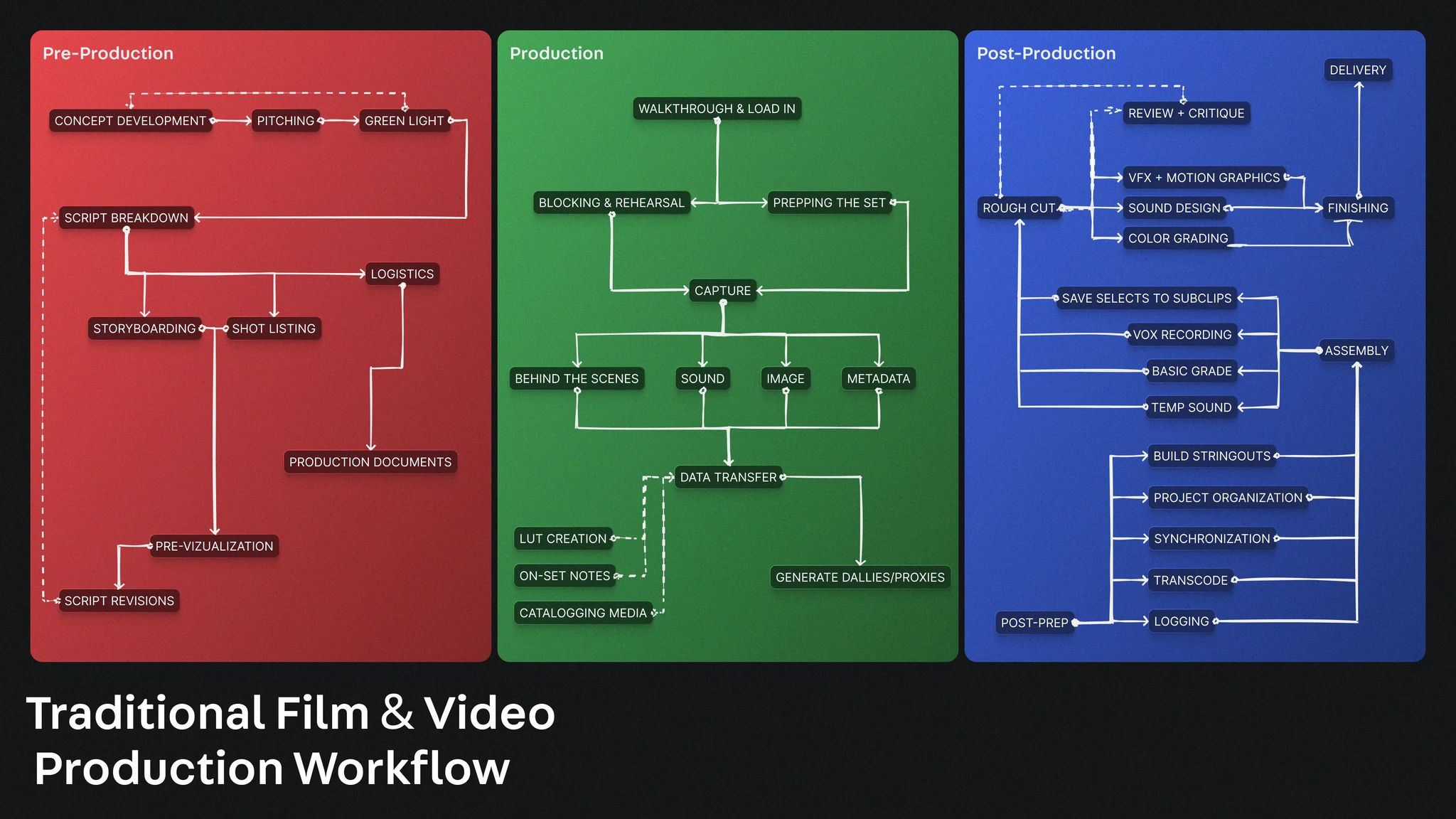

The Traditional “Waterfall” Production Workflow Is Inefficient

Imagine the typical pre-production to production to post-production process we’ve come to know well throughout the last century of motion pictures. Sure, there are things that have updated here and there over the years, but at a high level it’s remained unchanged from this process:

- Try to build out a vision and communicate it to other people with static documents like scripts and storyboards

- Hand that off to an army of people to capture it into data

- Dump the data into editorial and let them sift through it to pull out the best version of the story

While this has proven to be a viable process to make movies, it is wildly inefficient. Treating all the members of production (except for a select few) as boxed-in cogs in a machine leads to a struggle to see the whole picture of a project at any given time. Even worse, none of the standard pre-production methods are ever representative of what you’re actually working towards: a motion picture where sound and image play out over time.

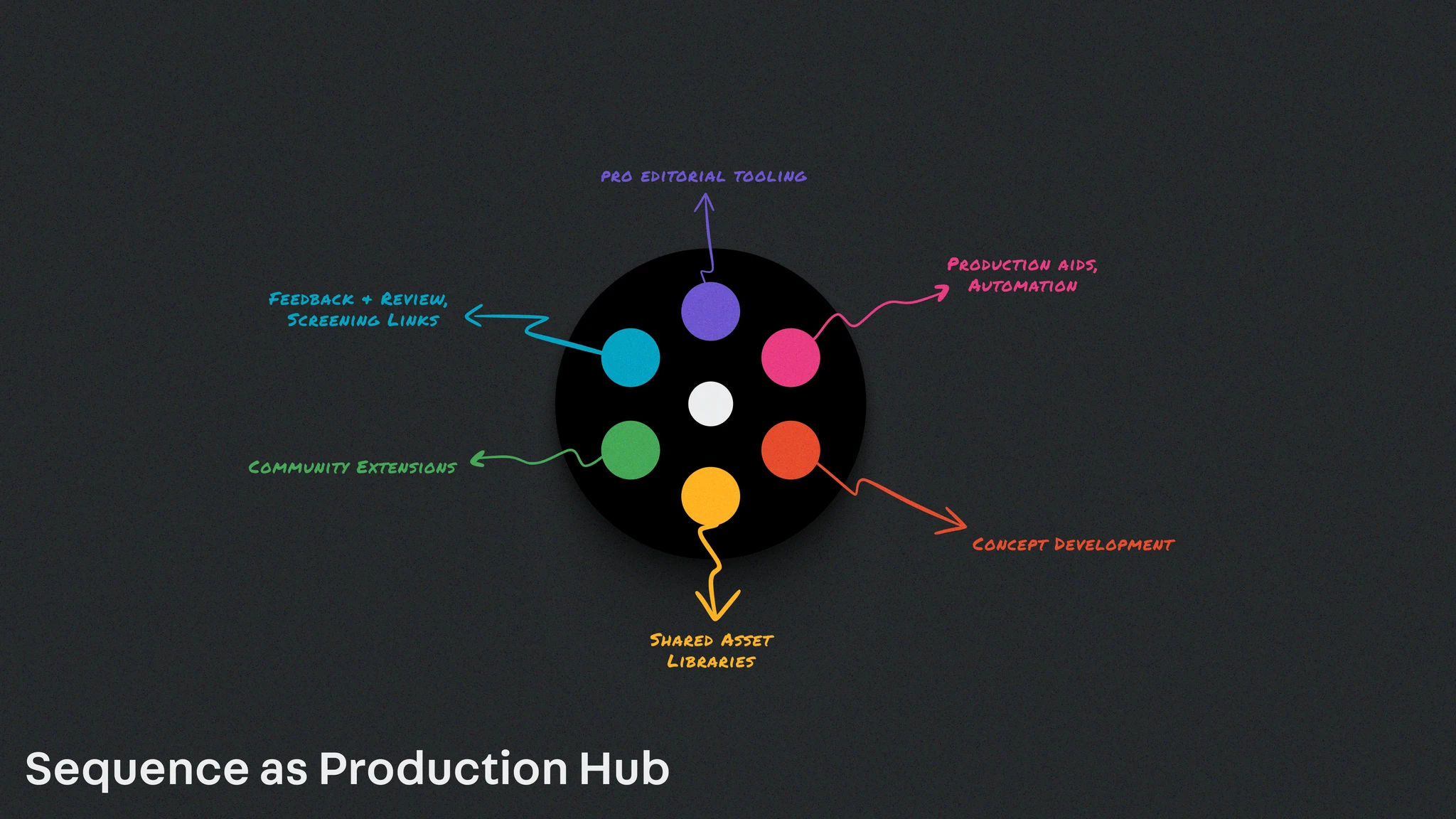

A central “production hub” could untite disparate pieces and people of the production process

The first step to solving this is throwing away the notion that because someone has a particular specialty, their work needs to happen in isolation. In an ultra-connected world, there’s no reason why information regarding a project can’t be united under a single digital umbrella, with specialty interfaces to address the needs of particular roles and workflows.

Okay cool, so we can centralize everything into some cloud database. We’ve just made cloud storage branded for creatives, big whoop.

Wanna know a secret? A timeline in any video app is just a database. Well, maybe not JUST a database, there’s the whole actually working with the media part. But in terms of data, all video apps are doing is looking at a giant database of media files, and saving a set of instructions for how to piece those files together, then showing you a representation of that graphically in the timeline. A timeline is a database.

When you start to imagine the timeline as a database whose content is populated by anyone involved in a project, the scope of what belongs in a timeline becomes a lot more interesting. Why do we wait to put things into a timeline until the third stage of production, instead of from the beginning?

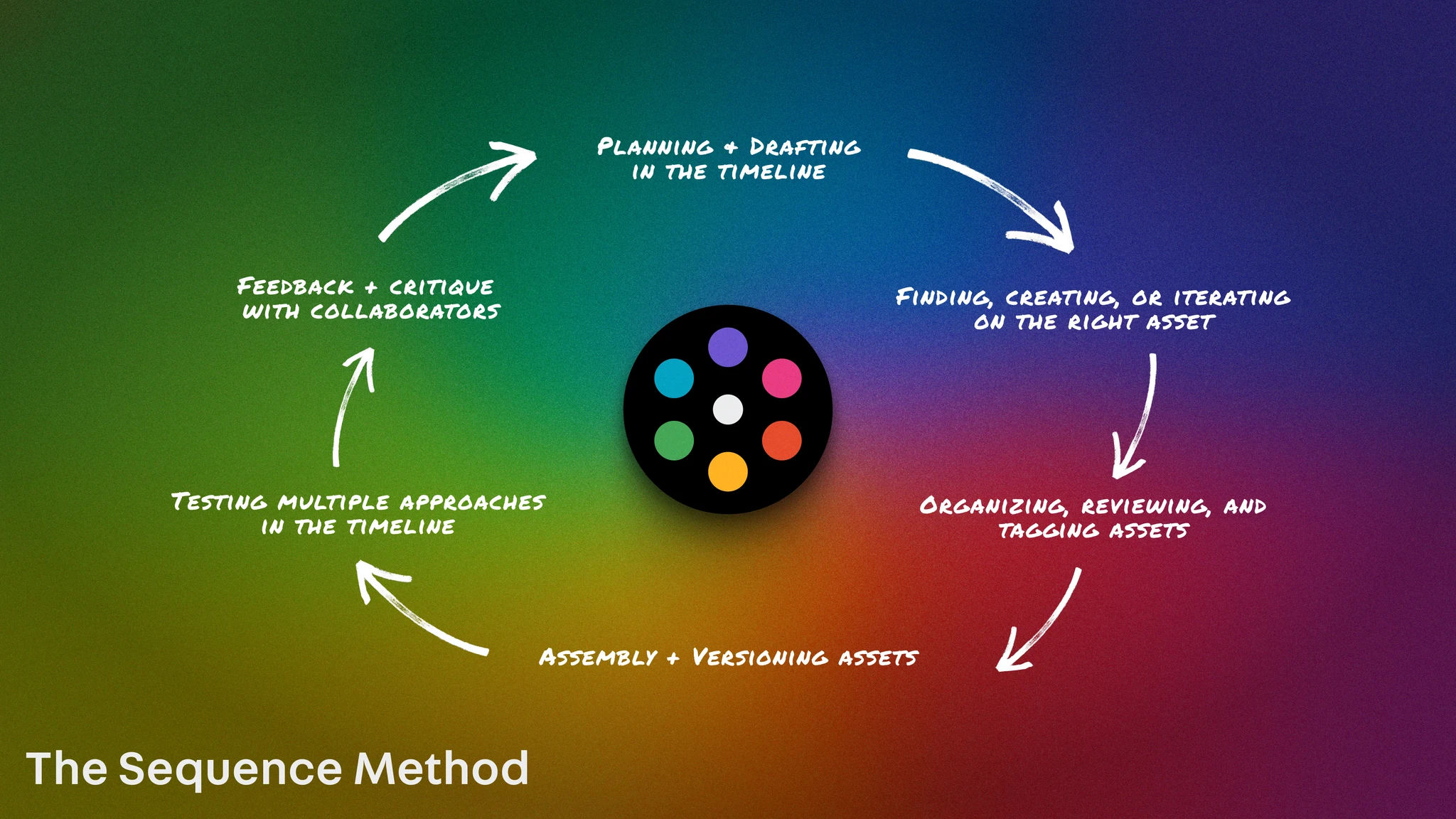

We need to rething the role of editorial to turn the production hub into the source of truth

When Pixar began creating the first animated feature film “Toy Story” (1995), there was a question by many about what exactly the editor would do. After all, editors working in live action had always been seen as the people who took hundreds of hours of raw footage and trimmed it down. Surely with Pixar using CGI to make exactly the shots they wanted, the role of editorial would be minimized.

However the ability to make any shot of the imagination happen easier than before didn’t suddenly mean filmmakers were faced with less material to cut down, it meant they were faced with every possible option ever to sort through. As such, it became the role of the editor to shape and test these million decisions before fully committing to animating them.

Instead of carving a feature-length runtime from hundreds of hours of live-action material captured on set, the animation editor starts in a void and must actively build a conception of the film before it is shot, with storyboards, or “unfinished comic book panels,” as editor Bullock describes them. Up to 75% of a Pixar film’s production timeline is filled with those storyboards made from pencil (or now, digital) sketches drawn by story artists, from which the editors construct, along with dialogue, a compelling, entertaining Story Reel experience. If it “plays” in pencil poses and non-professional performances, it will “sing” in Technicolor, voiced by stars.

For Pixar, the script itself is useful and storyboard panels are interesting enough, but the true star of the show is the timeline. This process, which came to be known at Pixar as the “edi-storial” process, moved the editorial teams from the end of production to the center of production, and turned the timeline into a living scratch pad for everyone to bring their ideas to.

This type of environment is difficult to replicate outside of computer animated films though, and it’s about time we did something about that.